Teaching haiku poetry offers a unique opportunity to explore a form of literature that combines simplicity with depth. Originating in Japan, haiku are brief poems that traditionally capture a moment in nature through a distinct pattern of syllables.

The art of haiku lies in its compact expression and the profound observation of the every day, making it an accessible and engaging form for students of all ages.

Related: For more, check out our article on The Best Poetry Books For Teachers here.

Approaching the teaching of haiku requires an understanding of its structure and cultural roots. A haiku is composed of three lines with a syllable pattern of five-seven-five.

While it is important to adhere to this structure, the essence of haiku poetry goes beyond syllable count; it’s about capturing a fleeting impression or a thoughtful insight into nature or human experience.

When planning to teach haiku, it’s valuable to prepare examples that illustrate this poetic form’s aesthetic and thematic range.

Key Takeaways

- Haiku poetry, with its Japanese origins, offers a succinct form for expressing the nuances of nature and human emotion.

- The structured pattern of five-seven-five syllables should be adhered to, but the deeper goal is to evoke a moment’s essence or emotion.

- Effective teaching includes carefully selecting themes that resonate with students, thereby fostering a deeper engagement with the art of haiku creation.

Related: For more, check out our article on How To Write A Poetry Lesson Plan here.

Historical Background of Haiku

Understanding the historical context of haiku allows educators to impart a deeper appreciation for this poetic form. It shapes the way haiku is both taught and understood, beyond its simple structure.

Origin in Japan

Haiku (俳句) originated in Japan, evolving from a traditional collaborative poetry form known as renga. Its history extends back to the Edo period where it began as the opening stanza of renga.

This opening stanza, called hokku, eventually gained independence and transformed into what is now known as haiku. These brief but expressive poems encapsulate the Japanese aesthetic of simplicity, nature, and momentariness.

Related: For more, check out our article on Poetry Rhyming Schemes here.

Evolution of Haiku Poetry

Over centuries, haiku has undergone significant stylistic changes. Notably, it was Matsuo Bashō in the 17th century who elevated haiku to a refined art form. His contributions infused haiku with a philosophical and transient beauty, often centring around the natural world.

As the form evolved, poets like Yosa Buson and Kobayashi Issa further contributed to its development. In modern times, haiku has transcended its Japanese origins, influencing writers around the globe and adapting to various languages and cultures.

It remains an exercise in precision and clarity, capturing fleeting moments of existence in mere seventeen syllables.

Understanding Haiku Structure

To master the art of haiku, one must first grasp its defining structure: a terse form that still resonates with depth and meaning through its unique pattern of syllables and lines.

The 5-7-5 Syllable Pattern

Haiku poetry is known for its distinctive 5-7-5 syllable count across its three lines. The first and third lines contain 5 syllables each, while the second line has 7 syllables.

This rhythm is pivotal as it creates a concise yet melodious flow that is characteristic of traditional haiku. The pattern is more than a mere word count; it’s about capturing a moment in time with efficiency and impact. It challenges the writer to express complex ideas and emotions with a limited number of syllables.

The Significance of Three Lines

The three-line structure of haiku is crucial for its poetic form. These lines work together to convey a single, poignant image that is often reflective of nature or human experience. Each line serves a distinct purpose:

- The first line sets the scene, often introducing the topic or an image to the reader.

- The second line serves to build upon the image or introduce a juxtaposition.

- The third line provides completion, often offering an unexpected insight or a twist, bringing closure to the haiku.

This tripartite approach not only simplifies the visual format but also encapsulates a full but fleeting moment of observation into a powerful literary snapshot.

Planning and Preparing to Teach Haiku

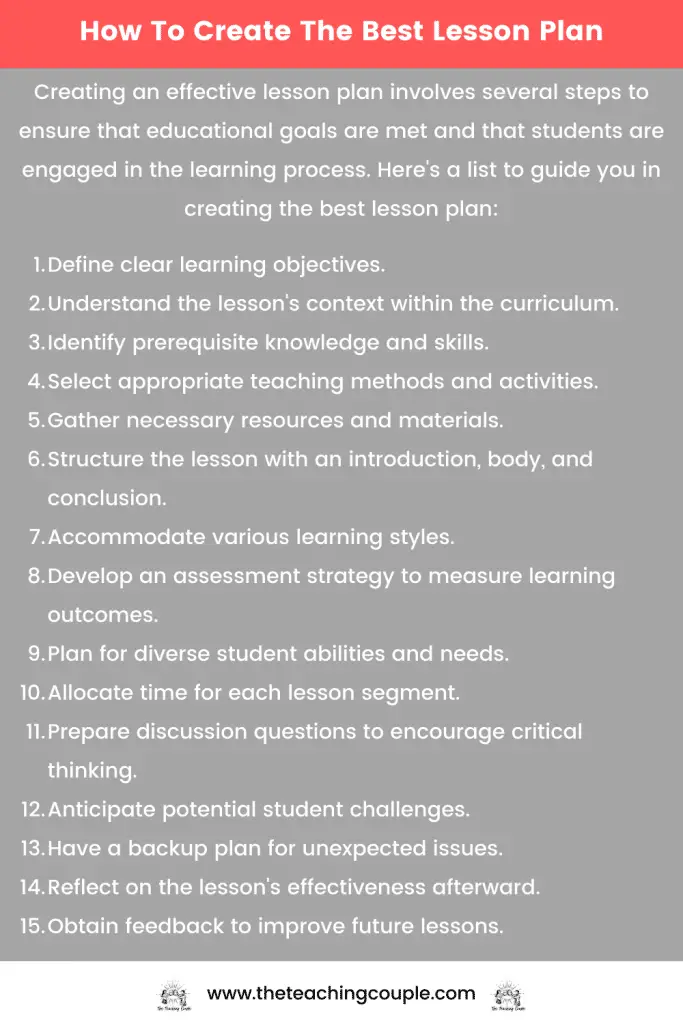

Before engaging students in the world of haiku poetry, teachers must carefully plan their approach. A well-structured lesson plan and the right materials are critical in conveying the essence of this poetic form.

Developing a Lesson Plan

For a successful haiku lesson, instructors should establish clear objectives that outline what the students should understand by the end of the session. It begins with an introduction to the origins and structure of haiku, typically featuring three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern.

Teachers should include a variety of activities such as analysing famous haiku examples, recognising the importance of imagery, and understanding the use of seasonal references (kigo).

An effective lesson plan may also incorporate individual or group writing exercises, providing opportunities for creativity and immediate application of the haiku format. Inclusion of a peer review segment can facilitate critical thinking and collaborative learning.

Materials and Resources

When collecting materials and resources for teaching haiku, educators should prepare a range of items to support the lesson. This can include:

- PowerPoint presentations outlining haiku structure and examples

- Printable haiku planning sheets for drafting poems

- Collections of haiku poetry for read-aloud sessions and analysis

- Visual aids and images to inspire poetic imagery

Teachers can also enhance the learning experience by utilising a pre-made lesson pack that often includes detailed instructions, worksheets, and additional activities tailored to teaching haiku poetry. These packs can be significant time-savers and are typically designed to align with educational standards.

Themes and Topics in Haiku Writing

In teaching haiku poetry, educators focus on themes that echo the origins and essence of this form, centring on nature and seasonal changes as well as the use of linguistic tools like kennings and metaphors.

Exploring Nature and Seasons

Nature serves as the cornerstone of haiku writing. These poems traditionally encapsulate brief moments in time, often relating to the natural world or the seasons.

Students may be encouraged to observe their surroundings, noting the subtle shifts in weather or the details in a landscape to convey depth within the confines of haiku’s structural brevity.

A haiku might feature the chirp of a bird in spring or the rustle of leaves in autumn, encapsulating the season’s essence in vivid imagery.

Introducing Kennings and Metaphors

Through kennings and metaphors, haiku poetry gains layers of meaning and beauty. A kenning is a compound expression in Old English with metaphorical meaning, like “whale-road” for the sea, and its use can enrich haiku by evoking powerful images in just a few words.

Students can be encouraged to develop their own kennings or use metaphorical language to distil complex emotions or scenes into haiku’s limited syllabic form.

For example, calling the moon a “night’s lantern” in a haiku intertwines metaphor with the poem’s focus on nature.

Engaging Students in Haiku Creation

Teaching haiku poetry to middle school students involves creating opportunities for them to explore and express creativity. Writing exercises and guided activities are essential for students to grasp and enjoy the experience of haiku writing.

Writing Exercises for Middle School

Visual Stimulation: Teachers can provide stimulating visual prompts, such as photos of nature, to inspire students.

This stimulates their imagination, encouraging them to write a haiku that captures the essence of the image. For example, a slideshow of autumn leaves or a mountain stream can evoke sensory details and emotions conducive to haiku.

- Word Banks: A list of words related to a theme can help students get started. These banks serve to spark ideas and provide students with language specific to their haiku topic.

Example:

- Nature Theme Word Bank:

- Whispering Wind

- Rustling Leaves

- Chirping Cricket

- Blooming Flower

Guided Haiku Writing Activities

Structured Writing Frames: Educators can utilise structured writing frames to guide students through the haiku creation process. This involves providing a scaffold that outlines the 5-7-5 syllable pattern of a haiku.

- Syllable Counting Practice: Students often benefit from exercises that focus on counting syllables, as it hones their ability to write within the haiku’s strict structure. Interactive games or clapping exercises can make syllable counting a fun and engaging activity.

Example:

- Line 1: [5 syllables] Majestic mountains

- Line 2: [7 syllables] Reaching into clouds above

- Line 3: [5 syllables] Whisper to the sky

These exercises ensure middle school students engage with the critical elements of haiku writing: sensory language, brevity, and the natural world, creating a strong foundation for their poetic expression.